by Wendy M. Stevens

by Wendy M. Stevens

My husband, Jim, and I had just finished our graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, moved to Decorah and were excited to hear that there were plans to start a food co-op called the Oneota Community Food Cooperative. The first Earth Day had been celebrated in 1972, the Vietnam War was winding down, and young adults throughout the country were opting to make their future less materialistic as they headed back to the land and vowed to return to a simpler way of life.

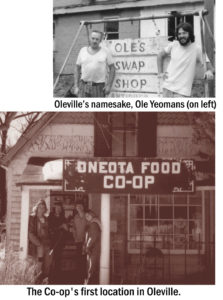

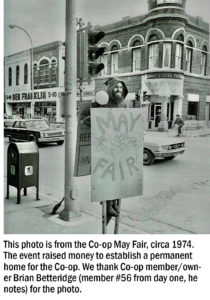

We were some of the first Co-op members as is evident by our Co-op member number: 16. You may know that at first the Oneota Community Food Co-op was housed in a very modest (this adjective is generous), barely two-story house in Oleville, not far from the UPS terminal. As was true of most co-ops of the 1970’s, you needed to be a member to shop there; some members volunteered in exchange for a discount on purchases and others were non-volunteering members. In the beginning the volunteers ran the day-to-day business of the Co-op.

We were some of the first Co-op members as is evident by our Co-op member number: 16. You may know that at first the Oneota Community Food Co-op was housed in a very modest (this adjective is generous), barely two-story house in Oleville, not far from the UPS terminal. As was true of most co-ops of the 1970’s, you needed to be a member to shop there; some members volunteered in exchange for a discount on purchases and others were non-volunteering members. In the beginning the volunteers ran the day-to-day business of the Co-op.

At the start, the key to the Co-op was hung on a nail inside the door of the woodshed behind the Co-op. The volunteer would get the key, open the Co-op and check the “short list” – the list of food items that were running low and needed to be ordered. One of the food items on the short list (such as the third one from the bottom) would indicate in which trash can the cash box had been hidden the night before. Clean metal trash cans with tight-fitting lids were how the 50 pound bags of flour, rice, beans, and oatmeal, etc. were kept. The tear string at the top of the bag was pulled and the open sack in the trash can was available for the customer to scoop out of. Just about all of the food was in bulk – in fact, that was one thing that we liked a lot, the ability to bring our own containers to fill and not have commercial packaging. The tight-fitting lids on the trash cans were important because another job of opening the store was to find and empty any of the rat or mouse traps that had caught unwanted critters overnight.

It was probably no surprise that eventually, someone used the available woodshed key to enter the Co-op and abscond with the cash box. So after that, the volunteer in charge for the day needed to stop by Bill and Chris Moorcroft’s house (Chris was the Co-op treasurer) to pick up the key and the cash box to open up for the day.

When necessary, the Co-op was heated with a wood stove during the day, thus the woodshed out back. One time the Co-op got a box (25 pounds perhaps) of rancid Brazil nuts. That day we heated the Co-op with Brazil nuts that burned hot and bright in the wood stove. At night there was an oil burner to keep the main part of the Co-op from freezing. The volunteer needed to turn on the oil and after a number of seconds, throw in a lit kitchen match. If all went well, there was an audible poof as the oil lit. I understood wood stoves. Lighting the oil burner, on the other hand, was not my favorite activity. There was a prep sink in the backroom, away from the heat sources. It was important to have electric heat tapes wrapped around the pipes to the sink or they would freeze and sometimes break in the winter, and water would flood the floor of the back room.

I don’t think that we sold any fresh produce, but we did sell cheese that came in five pound blocks. The volunteer on duty went behind the cheese display cooler to cut whatever amount the customer wanted. Iduna Field was the dentist’s wife and very particular about what she expected. One day when I was working, she asked for one pound of a certain cheese. I was sort of terrified of her to start with, but I figured that one pound of cheese should be about the same size as one pound of butter. So I cut a piece that size, and she immediately told me “That’s too small.” Well, I put it on the beam-balance scale and was so relieved when the needle came exactly to where it should be for one pound.

Meeting people was one of the most interesting and memorable aspects of working at the Co-op. I believe a person could shop at the Oneota Food Co-op if they were a member of another coop. At that time, Jim and I lived in Decorah, and I was rather glad that we didn’t own land in the country. It was not unusual for a Volkswagen bus to pull up in front of the Co-op and several hippie types get out and ask if anyone had land in rural Decorah where they could camp for a while (and also enjoy the bounty of the garden – although they didn’t say that part) as they were traveling through.

Meeting people was one of the most interesting and memorable aspects of working at the Co-op. I believe a person could shop at the Oneota Food Co-op if they were a member of another coop. At that time, Jim and I lived in Decorah, and I was rather glad that we didn’t own land in the country. It was not unusual for a Volkswagen bus to pull up in front of the Co-op and several hippie types get out and ask if anyone had land in rural Decorah where they could camp for a while (and also enjoy the bounty of the garden – although they didn’t say that part) as they were traveling through.

One day while I was working, a young man and his mom came into the Co-op. He was visiting from The Farm, an intentional community of families and friends in southern Tennessee. At that time there were enough diverse people (farmers, doctors, various craftspeople) living at The Farm, so they did not use money. Everything was obtained by barter, so the mother of this young man was going to buy a few things from the Co-op for him. Meanwhile another customer, a young pig farmer, came into the Co-op, and it turns out that they had both gone to Decorah High School together. The talk turned to babies, and I will never forget the look on the pig farmer’s face when the young man from The Farm said he wasn’t married but his infant daughter’s name was Lavender Morning.

I don’t think any of us imagined that 50 years later, the Oneota Community Food Cooperative would be a highly regarded, cornerstone business on Water Street in downtown Decorah. The first years were a true experiment where we improvised when necessary, often in less than desirable conditions. Not all co-ops that were started in the mid-1970’s survived – in fact, many didn’t. Oneota Community Food Co-op was “lucky” in that from the beginning until today, it has had dedicated members that were determined to see it succeed. Here’s to another 50 years of the Oneota Community Food Cooperative serving Decorah, and deep inside, I hope that Lavender Morning has found herself in a similar co-op community.